Understanding and practicing inclusion at the interpersonal level

Microaggressions are ‘everyday’, subtle, often unintentional comments or actions that communicate bias, prejudice or a stereotype toward individuals from marginalized groups. They may seem minor, but over time, their cumulative effect can cause significant psychological, physiological and societal harm.

Microaggressions:

- reinforce stereotypes;

- undermine professional and social confidence;

- create unwelcoming or unsafe environments in schools, workplaces, and communities;

- are often normalized – treated as jokes, misunderstandings, or overreactions, often left unchallenged – which is why it’s critical to recognize and disrupt them early.

Depending on the context, the following remarks may be considered microaggressions:

- Asking a person of color, “Where are you really from?”

- This question may convey the message that the person doesn’t truly belong and is perceived as a foreigner based on their appearance or ethnicity, even if they may have been born here. It can undermine their identity and communicate exclusion, even if unintentionally. Over time, such messages can contribute to feelings of alienation.

- Saying to a female colleague, “You’re very assertive– for a woman.”

- This remark reinforces sexist stereotypes by implying that assertiveness is unusual or inappropriate for women. It subtly penalizes women for traits that are praised in men, discouraging leadership and self-expression. The comment upholds gender-based behavioral expectations.

- Commenting on a disabled person’s ability in a way that’s patronizing: “You’re so inspirational!”

- Praising a disabled person for routine actions can be patronizing, reducing their identity to a source of inspiration for others. It shifts focus from their individuality to their disability. While often meant kindly, it objectifies and diminishes their everyday agency.

- Saying about a Roma student: “How does the gypsy girl perform better in class than the other students?”

- This comment reinforces negative stereotypes about Roma people – implying that they are less intelligent and therefore less successful in education – whilst also discrediting the outstanding academic achievement of the Roma student. This remark also includes the out-dated term ‘gypsy’, which is by many considered to be an offensive racial slur due to its negative connotations.

- Microaggressions can also be non-verbal. For example, clutching your bag or crossing the street when a Black man walks by.

- This action nonverbally communicates fear and suspicion, based solely on the person’s race and gender. It reinforces the harmful stereotype that Black men are inherently dangerous or criminal. Even if done unconsciously, repeated exposure to this behavior sends the message: “You are not safe to be around” – which is dehumanizing and stigmatizing.

While these remarks and actions may not be intended to harm, their impact remains negative regardless of intent. It is typically not a single remark itself that causes harm, but the pattern of being repeatedly confronted with the same remarks or stereotypes on a frequent basis. In a way, microaggressions are like mosquito bites: one might not bother you, but getting bitten repeatedly, every day, can wear you down:

- Psychologically, repeated exposure leads to chronic stress, anxiety, and symptoms of depression, as individuals internalize feelings of exclusion, devaluation, or hypervigilance in everyday interactions (Sue et al., 2007).

- This persistent stress doesn’t remain in the mind– it can manifest physiologically: discrimination, as a social stressor, can cause elevated blood pressure, increased heart rate, and the secretion of certain hormones, such as cortisol (James-Bayly, 2023).

In academic and professional settings, microaggressions can undermine motivation, concentration, and confidence, leading to a weakened sense of belonging, impaired performance, lower satisfaction, and increased likelihood of attrition and turnover.

The harm caused is thus not only personal, but also affects institutions, as environments that tolerate microaggressions often struggle to retain diverse talent and foster truly inclusive cultures.

Moreover, microaggressions aren’t just isolated annoyances— they are part of a broader system of bias and discrimination. Every time we ignore or excuse subtle bias, we reinforce a system where bigger harms become more acceptable.

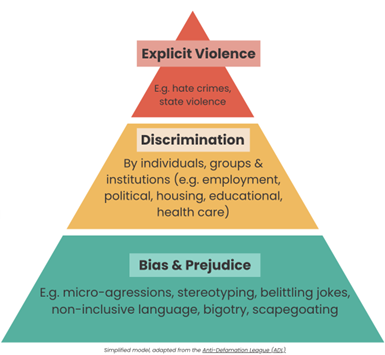

The Pyramid of Hate, developed by the Anti-Defamation League (see figure 7 for a simplified adaptation), illustrates how individual attitudes and behaviors, if unchecked, can contribute to increasingly explicit forms of bias and violence. At the base are implicit biases, stereotypes, and microaggressions– everyday expressions of prejudice that are often dismissed as harmless or unintentional. But when these are normalized and tolerated, they begin to shape the social climate, reinforcing the idea that certain groups are “less than,” “foreign,” or “suspicious.” Over time, these biased attitudes lay the psychological groundwork for more overt acts of discrimination, such as exclusion from opportunities, unequal treatment, or institutional policies that disadvantage marginalized groups.

As this climate of normalized bias intensifies, it becomes easier for more extreme expressions (e.g. verbal harassment, hate crimes, or state-sponsored violence) to emerge and even gain social acceptance. The key message here is that bias doesn’t begin with violence– it begins with silence. Stopping the escalation means interrupting harmful behaviors and narratives early, at the everyday level.

An active bystander is someone who not only witnesses a problematic situation but chooses to speak up or take action. Bystanders have the power to challenge harmful norms, support those affected, and signal what behavior is acceptable in a group or environment.

When you witness a microaggression or other unacceptable behavior, you may use one or more of the 5Ds– five practical strategies from bystander intervention research (Burn, 2009; Fenton et al. 2014; Right To Be, n.d.):

- Distract – Shift the focus to de-escalate.

“Sorry to interrupt– can I grab you for a quick sidebar?” - Delegate – Involve someone else with more authority.

“Can we check in with HR/management about that comment?”

- Delay – Check-in with and support the person after the incident.

“I saw what happened earlier– are you okay?” - Document – Take notes or record a video of a public incident (if legal, safe and appropriate to do so) as a witness testimony or proof

“I recorded / wrote down what happened – what would you like me to do with it? Would you like help reporting this incident?” - Direct Action – Address the behavior head-on.

When taking Direct Action and addressing the person causing the incident directly, these are some examples of strategies that you could employ in the moment, depending on the context:- Address → “I see this happening, and I am uncomfortable with it.

- Challenge → “I don’t think what’s happening here is okay.”

- Question → “What exactly do you mean by that?”

- Explain/educate → “This is why what is happening here is not okay.”

- Correct → “What you are doing is not okay.”

- Check interpretation → “This is what I think you said/did, is this what you meant?”

Fusion comedy & TheTeacherColeman (2018). “How microaggressions are like mosquito bites • Same Difference (Clean)”. [Youtube video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nQ9l7y4UuxY

- Understanding what microaggressions and their effects are, in turn fostering a sensitivity that can help recognize and act upon them better

- Reflect on and/or practice different context-dependent strategies to use when witnessing microaggressions and other inappropriate behavior as a bystander.

Below are three activity ideas, to be led by a facilitator in groups in workshop or class settings, to reflect on and/or practice interventions against microaggressions. The facilitator can choose and adapt one or multiple activities to fit the needs of the group and situation.

For who: Large or small groups of participants (staff, students, etc.) with varying levels of awareness. Also ideal for workshops with limited time for interactive activities.

Instruction:

- Introduce the concepts of microaggressions and active bystander using the information, slides and resources of this module.

- Ask participants to reflect in pairs (5 min) on moments where they may have experienced, witnessed, or (unintentionally) contributed to a microaggression. Encourage them to consider these roles:

- Receiver: Were you ever on the receiving end?

- Sender: Have you ever realized you said or did something (unintentionally) harmful?

- Bystander: Have you witnessed a microaggression? Did you respond?

- Afterwards, invite participants to share reflections with the full group (10 min) to have an open discussion, share insights and identify common themes.

- Tip: Remind participants to respect confidentiality and only share what they’re comfortable sharing.

- Finish with summarizing different intervention strategies (e.g. those in the module) and emphasizing that there is no ‘right’ intervention, as they are all context-dependent.

For who: Large or small groups of participants (staff, students, etc.) with varying levels of awareness. Also ideal for workshops with limited time for interactive activities.

Instructions:

- Introduce the concepts of microaggressions and active bystander using the information, slides and resources of this module.

- Present a realistic scenario on the slide involving a microaggression (e.g., a biased comment in a team meeting). Offer multiple-choice options representing different bystander strategies.

- Invite participants to discuss, optionally first in pairs, then with the larger group what would they do and why? What impact each choice might have?

- Finish with summarizing different intervention strategies (e.g. those mentioned in the module) and emphasizing that there is no ‘right’ intervention, as they are all context-dependent.

Example 1: During the weekly team meeting, the discussion focuses on how to better reach underrepresented groups. While reviewing the profile of these groups, you notice that several colleagues express various assumptions and stereotypes about them. When would you say something?

A: I wouldn’t.

B: After the first comment.

C: After the most hurtful comment.

D: After the meeting.

E: Other…

Example 2: During lunch, Colleague A makes a joke that was meant in good fun, but Colleague B finds it hurtful. When Colleague B says they didn’t appreciate the joke, Colleague A responds with, “Oh come on, don’t be so sensitive—it was just a joke! You can’t say anything these days without someone taking offense. How would you respond as a bystander?

A: I wouldn’t – it was just a joke.

B: I would say the joke was very inappropriate and that he can’t say that.

C: I would say the joke made me feel uncomfortable.

D: Other…

For who: Medium-sized groups of participants (staff, students, etc.) who are looking to experiment with strategies, understand what feels authentic, and build confidence as an active bystander in a supported environment.

Instructions:

- Introduce the concept of microaggressions and active bystander using the information, slides and resources of this module.

- In small groups, invite participants to discuss real or fictional microaggression scenarios from work, school, or social settings.

- Prompt: “What is a situation where you wish you had spoken up, but didn’t?

- Ask participants in each group to choose one scenario emerging from their conversations to develop into a short role play. Make sure they include three roles:

- Sender (perpetrator; person who makes the microaggressive remark)

- Receiver (target of the microaggression)

- Bystander (initially passive)

- Once all groups have developed one case, invite each group to present their ‘base scene’ to the full group. The base scene is how the situation actually played out without (or with an ineffective) intervention.

- Invite the whole group to vote on the case that they would like to explore further. This will be the case that will be used for the rest of the session.

- Once the case has been selected, multiple rounds will be played:

- Round: Invite the participants to perform the scene as it originally happened once more. All those who are not playing, are active observers.

- Round and onward: Re-play the same scene, but invite observers to take over different roles and step in to try different bystander strategies.

- Finish with summarizing different intervention strategies (e.g. those in the module) and emphasizing that there is no ‘right’ intervention, as they are all context-dependent.

Tip: Offer positive feedback and focus on learning– not performance.

Lui, P. P., & Quezada, L. (2019). Associations Between Microaggressions and Adjustment Outcomes: A Meta-Analytic and Narrative Review. Psychological Bulletin, 145(1), 45–76.

Skinner-Dorkenoo, A. L., Sarmal, A., André, C. J., & Rogbeer, K. G. (2021). How Microaggressions Reinforce and Perpetuate Systemic Racism in the United States. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(5), 903-925. https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916211002543

Solórzano, D. G., & Huber, L. P. (2020). Racial microaggressions: Using critical race theory to respond to everyday racism. Teachers College Press.

Sue, D. W. (2010). Microaggressions and Marginality: Manifestation, Dynamics, and Impact.

Sue, D. W. & Spanierman, L. (2020). Microaggressions in Everyday Life: Race, Gender, and Sexual Orientation.

Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M., Torino, G. C., et al. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271–286. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271

James-Bayly, Savannah. (2022). “Microaggressions: Why and How do they Impact Health?” Medical News Today. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/microaggressions-how-and-why-do-they-impact-health#Microaggressions-direct-impact-on-health

Dilemma Game app, developed by Erasmus University Rotterdam – contains many examples of workplace microaggressions. https://www.eur.nl/over-de-universiteit/beleid-en-reglementen/integriteit/wetenschappelijke-integriteit/dilemma-game

Burn, S. M. (2009). A situational model of sexual assault prevention through bystander intervention. Sex Roles, 60(11–12), 779–792. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-008-9581-5

Fenton, R. A., Mott, H. L., McCartan, K. and Rumney, P. (2014). The Intervention Initiative. Bristol: UWE and Public Health England

Right To Be (n.d.) The 5Ds of Bystander Intervention. https://righttobe.org/guides/bystander-intervention-training/

Scully, M., & Rowe, M. (2009). Bystander training within organizations. Journal of the International Ombudsman Association, 2(1), 1-9.